Hello everyone,

It's time for another status report. Our blogpost from last year and the subsequent talk at rC3 dealt with the general handling of game data with nyan and our modding API. This year, we focused on implementing the parts of the engine that actually do something with the data... and also everything else necessary to make it usable. And how hard could that be, right?

Current state

While the gamestate is integral for creating the game mechanics that define the games, other core modules are equally as important for getting things to work. The gamestate module just drives the simulation of the game world. It takes events and handles them based on certain rules (i.e. it is responsible for gameplay). However, it is not concerned with user inputs or outputs. That's what the other modules are for:

- Renderer: Shows what's happening in the game on your screen. It receives positional information and graphic assets from the gamestate and decides when and how to display them.

- Presenter: Despite its name, it's not only used to "present" things, but also for receiving user inputs. The presenter module manages local user input and output for everything that is not graphics. For example, it translates all the key presses and mouse clicks to game events.

- Network: Receives network packages for a multiplayer game and feeds them into the local simulation, i.e. the gamestate and eventsystem modules.

- Eventsystem: Manages and tracks events in the engine and ensures that they are properly ordered (the latter is important for receiving network events).

- WorldUpdater: Applies events to the game world.

All of these modules have to communicate and work together for creating a functional (multiplayer) game. In openage, the core modules will be loosely coupled, i.e. we try to minimize their dependencies on each other. We do this on the one hand to allow for flexibility for extensions or changes in the future, preparing the engine for low-level modding. On the other hand, we hope a loose coupling keeps the code maintainable and prevents the engine from evolving into a giant spaghetti monster.

Gamestate: How we do ingame things (Recap)

For those still unfamiliar with our game data handling, we recommend the rC3 talk again which goes much more into detail about this. For everyone else, here's a quick refresher on how the general workflow operates.

Ingame units have so-called abilities which define what they can do (e.g. move, attack, gather), what they are (e.g. selectable)

or what traits they have (e.g. attributes like HP). Abilities are assigned to a unit by adding the associated Ability

object to the unit definition in the modpack data. The Ability object also stores all necessary data related to that ability, e.g. a

gather rate for the Gather ability.

In the engine, every Ability object is associated with a gameplay system that can be accessed by the gamestate for

unit instances with the assigned ability. This system uses the data from the object, e.g. for Gather the gather rate,

to execute an action. In the case of a Gather ability, the action would be that a villager's resource storage is

increased by the gather rate value, while the targeted resource spot's resources are decreased.

Gamestate 2: Do many things and do them right

So far so good. In this basic model, every ability has a corresponding gameplay system which, when used, handles the necessary calculation to do the associated gameplay action. However, something that needs to be addressed is that most gameplay mechanics in AoE (and RTS in general) can often not be modelled as one single action. More precisely, gameplay mechanics often involve action routines that are executed in order. For example, an infantry attack in AoE2 actually involves at least two actions:

- Move to the target

- Attack the target

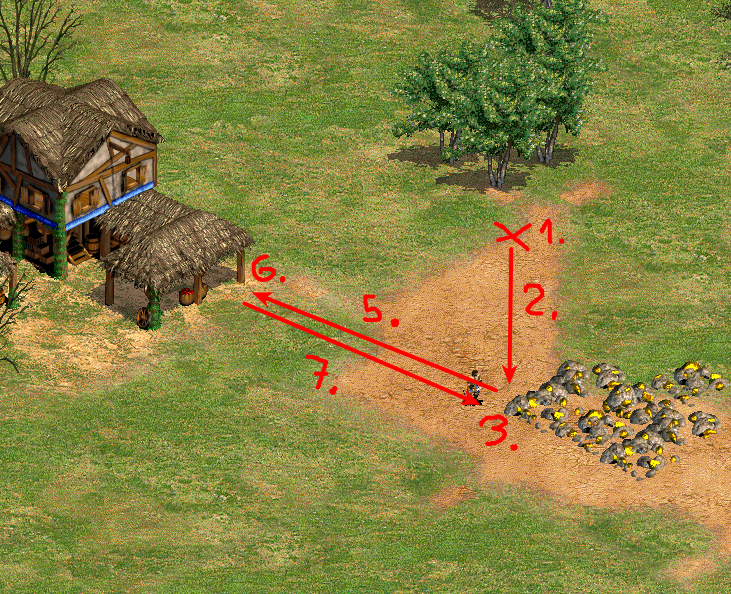

These routines can also be much more complex. Take the gathering mechanic in AoE2 for example, which we will break down for you.

- The player commands the villager to a resource (beginning of the task)

- Villager moves to the resource spot (Move action)

- this action continues until the villager arrives at the resource spot

- Villager starts gathering the resource (Gather action)

- this action continues until the villager's resource storage is full

- Search for a resource dropsite (technically not an action, but important for the routine)

- Villager moves to a resource dropsite (Move action)

- this action continues until the villager arrives at the resource dropsite

- Villager deposits the gathered resource at the resource dropsite (DropResources action)

- Start again at step 2.

As you can see, these routines can get quite complex. In this example, we have actions that end on a condition (step 2, 3 and 5), intermediary steps (step 4) and we even have to integrate a loop (step 7). Mechanics might also have branching paths based on certain conditions, e.g. a farm is only reseeded if the player has enough resources. Other actions, such as health regeneration for the unit, might also happen in parallel.

The solution we chose for this problem is to use flow graphs for handling these complex mechanics (or activities as they are called internally). We take advantage of the event-driven nature of our gamestate implementation here. Starting, ending or cancelling an action always involves an event. With the help of flow graphs, we can define what events start or end actions by mapping the events to paths in the flow graph. When an event happens, the appropriate follow-up action is started. How this would look like can be seen below.

Every action can be represented as a node in the directed flow graph. When a node is visited, the associated action is taken, i.e. the gameplay system executes. Paths between the nodes are mapped to events. The unit - in this case the villager - registers and listens for events that are required for advancing from the current node to the next node. For example, if the current node is step 3, the villager would listen for the event that its resource storage is full. When the event fires, the activity advances to the next node and the next action is taken. Although not depicted here, a node may have several outgoing paths that each map to a different action.

The nice thing about this solution is that it allows for sophisticated control over the flow of actions, while also being reasonably efficient in terms of memory and computation. The flow graph only has to be defined once for every unit type. Sometimes the flow graph for an activity can be the same for an entire class of units. For example, the AoE2 attack mechanics would use the same flow across every military unit. At runtime, the unit only needs to know its current node in the activity's flow graph as well as the events it needs to listen for. Advancing to the next action is a simple lookup for the next node, using the received event.

Renderer

In theory, the renderer module has a simple task. It gets handed animation IDs and positional arguments by the gamestate and draws them on the screen. openage, like AoE2 and other Genie Engine games, uses a 2D renderer, so animations are sequences of 2D images (sprites).

However, in practice the sprites are actually more than plain images. In AoE games, some of the pixels in a sprite are "special" and are used to convey gameplay information. For example, pixels can be marked as player colors or as an outline. How these pixels are displayed depends on the associated gameplay information, e.g. the player ID. This situation imposes two questions for us that we have to address. First of all, we need a way to mark the special pixels, so that the renderer knows they exits. Secondly, the renderer needs to know how to transform the special pixel into a color using the gameplay information.

We address the first problem by encoding special pixels in the pixel data itself. Sprites for openage are stored in PNGs using the 32 Bit RGBA format, where every color channel (red, green, blue and alpha) is 8 Bit wide and thus can have 256 possible values.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

To mark our special pixels, we change the interpretation of the alpha channel slightly. We reduce the alpha channel to 7 Bits and use the last bit as a marker bit instead. The marker indicates whether the pixel requires special processing.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

If the last bit is 1, the pixel is treated as a normal color and would be copied directly into

the drawing buffer. If it is 0, then the remaining 7 bits of alpha channel are

interpreted as an index for a special draw command. The 24 Bit of the RGB channels

may be used as a payload to store additional information such as a palette ID. Based on

the command index, the GPU can choose a corresponding code path to draw the special pixel.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

This effectively leaves us with 128 usable alpha values for normal colors and 128 assignable draw commands.

Now we need to tell the renderer, or rather the GPU, how to handle these commands. We do this by letting the renderer assign custom shader code chunks to each command index. At load-time, the renderer assembles the code chunks for all commands into the fragment shader that is uploaded to the GPU. When the fragment shader receives pixel data, it will first check the marker bit. If it's a command, then the shader will execute the predefined code chunk passed to the renderer at load-time. A side benefit of handling custom draw commands in shader code is that the commands can potentially be redefined by each modpack, i.e. they are not hardcoded into the engine.

For every command, we can define "associated gameplay data" that should be sent by the gamestate alongside the animation ID. For example, this can be the ID of the owner of a unit (to determine the player color). The information on how to find this data is defined in the modpack and stored in the engine's indexing system at runtime. When a system in the gamestate sends an animation request to the renderer, it will also look up all associated data using the information in the indexing system and attach it to the request.

![]()

(The final rendering result after processing all pixels. Red pixels are player color commands, green pixels are outline comands.)

Presenter: Game Control

To make games running on the engine playable by actual people, we have to translate the input events from the player's peripherals to game events usable for the game simulation. As stated in our introduction, this is part of the presenter module's responsibility. The presenter manages the peripherals as well as their configuration.

However, mapping input events to game events is not the only relevant task. Game control is also about the separation of concerns, specifically between ingame and outgame control information. An example for ingame control information is the command queue of a unit. This type of information is directly relevant for the game simulation as it affects the behaviour of units in the game world. On the other hand, outgame information is everything that mostly concerns the person in front of the screen, but does not affect the game world on its own. Example for this are the input devices of a player, the layout of the UI, but also control concepts like a selection queue for units. Outgame information can be used to influence the game simulation, but it should not be required to run it.

So, what's the point of having a separation of concerns here? Our main motivation is to generalize the interface to the game simulation, so that it is not limited to human players. In RTS games, humans are not the only actors that can exercise control. Possible actors could be an AI, a script, or a dedicated server in a multiplayer game. The outgame information (and outgame control) these actors posess can be very different, yet they should all be able to take control of ingame information in their own way. This is especially relevant to AI, since it should not be limited to human control methods.

Part of the solution to this problem is our model of "controllers". A Controller object is

a link between the outgame control methods and the game simulation. The main purpose of a

controller in this regard is to define the level of access control an outgame actor has over

ingame information. For example, a controller may define that a human player has control

over an ingame faction with a specific ID. It can also define the permissions the actor

has when accessing the ingame information. A spectator may only have "view" access to

an ingame faction, while the acting player of said faction has "view" and "action" access.

A nice benefit of handling access control like this is that we can easily switch control

between ingame factions by modifying or replacing the controller.

The second job of the controller is to map input events from the presenter to ingame events for the game simulation. For this purpose, the controller acts as an interface between the gamestate and presenter modules. The important thing is that the controller merely does the mapping and does not care about the type of input device. That way, all kinds of input events can be translated to the game simulation, whether they come from physical devices, an AI, a script, or a network socket.

Questions

Do you have something to discuss? Visit our subreddit /r/openage or pass by in our discussion board!

And you can reach us directly in the dev chatroom:

- Matrix:

#sfttech:matrix.org - IRC:

#sfttechon libera.chat

openage dev updates

openage dev updates